|

| God, do I love minimalist posters. |

To the average viewer of James

Swirsky and Lisanne Pajot’s Indie Game:

the Movie, the film appears to be just your typical underdog story, with

the filmmakers following four “indie game” developers – Jonathan Blow of Braid fame, Super Meat Boy developers Edmund McMillen and Tommy Referens, and

Phil Fish, the creator of the recent indie gem Fez – as they slave and strive for success. But such a simple summary of the film would

discredit what the entire documentary truly

represents, not just in the filmmaker’s decisions to show the true brilliance

of the developers on whom they focus, but also how the developers’ efforts have

an artistic meaning. The film also strives to dispel some of the

misconstrued ideas about video game culture and the people who make and play

games. For example, video games have often just been seen as a fun hobby to

many of the uninitiated masses, something to pass the time and/or alleviate

stress, but nothing to fully dedicate one’s life to. But, through their subjects, but also through

their brilliant camera and editing work, Swirsky and Pajot show that this “just

a hobby” theory is not true at all.

Video games are not just a hobby; they are a way of

life. Like any other artist, the games

are an expression of the creator’s ideals and life experiences. Therefore, these creators do not just work on

and off on these games like anyone else would treat a hobby; rather, like a true

dedicated artist, these men work endlessly to create enjoyable, meaningful, and

lasting experiences for their player. This

constant dialogue between creator and player, between artist and audience, as

well as a true elucidation of what video game culture becomes the grand truth

of the story.

|

| Pajot (Left) and Swirsky (Right) |

Let us just focus on the work of the

developers and what their projects truly mean to them. And, to answer that, we must ask the

question, “What is an indie game?” On a basic level, an independent (or

“indie”) game is a game that is not financially supported by any big name

publisher. As opposed to the better-known

titles such as Call of Duty or Mass Effect, an indie game is either

financed by the developers themselves, or by a variety of financers that do not

represent a company. For example,

Jonathan Blow’s Braid was financed

completely by Blow himself. However,

while that may be what be what an indie game is, what an indie game means

is quite different, and the answers to such a question might vary. A developer might make an indie game in order

to make friends, to communicate a specific message with the player, or to

express themselves and all of their hopes, fears, and vulnerabilities.

|

| Edmund, and one of his various forms of facial hair. |

Edmund

McMillen, the creative designer of the game Super

Meat Boy and one of the subjects of the film, represents this idea of

expression quite well as he describes one of his previous projects known as Aether.

The game follows a young child as he explores space with a strange,

octopus-like creature. As the boy

explores the various planets and stars, he meets many of the various planets

denizens, most of whom have problems or fears that the boy must solve. But, as the boy solves more and more the

creatures’ problems, the smaller the Earth becomes until he tries returning at

the end of the game, and the earth shatters under his weight. This concept might seem bizarre to the

outsider, but to Edmund, the game had deep artistic and psychological

meaning. According to Edmund, the game

itself is a commentary on the dangers of isolation and obsession, for the boy

is so focused on solving the creatures’ problems (which are the same problems

Edmund experienced as a child, including painful stomach aches and extreme

loneliness) that he forgets, and eventually destroys, his connection to Earth

and the real world. In many ways, this

reflected Edmund’s experiences as a child, when he lived with his grandmother due

to a poor relationship with his stepfather, and often felt isolated within

himself and his graphic artwork. To

truly convey how much this game means to Edmund, the filmmakers often compare

the gameplay of Aether to some of

Edmund’s childhood drawings, with one particular drawing of young Edmund

imagining himself in space eerily resembling the game as a whole, as if the

young Edmund knew he was going to make a game about this exact topic in the

future.

|

| Boy, that's the most adorable psychological trauma I have ever seen. |

Even

the game focused on in the film, Super

Meat Boy, has a large significance to Edmund. The filmmakers focus on Edmund’s face, and

also use clips from the game where the eponymous character dies over and over

in the game’s death traps. Solemnly, Edmund

admits that the character is not supposed to be a light-hearted character. With no skin and constant resurrections from grisly

deaths, Meat Boy feels only pain and dread of his next demise. But, there is more to it than that. The objective of the game is to rescue Meat

Boy’s girlfriend, who is made of bandages.

As Edmund explains how Band Aid Girl completes Meat Boy and takes away

his pain, the filmmakers drop heavy hints of this having a double meaning to

Edmund, as we see a woman’s hands sewing plush toys of the two characters. It is only after this explanation that we see

Edmund’s wife, who is his moral support, and the relief to the pain and

suffering that comes with his artistic mind and pursuits and the constant work

that comes with game development. In

many ways, the game presents itself as a love letter to Edmund’s wife and all

that she does for him. When Super Meat Boy is eventually a massive

success and critically praised, this is not only a victory for Edmund on a financial basis. As Edmund tearfully admits, the idea that a

child would stay home from school to play his game and be inspired by his

life’s work – just as old games were an inspiration to him as a child – is the

ultimate victory. He was able to put

himself out in the world, and was not only accepted, but also praised and even

adored. For a person who suffered all his life with isolation and escapism,

this acceptance means everything to Edmund.

|

| This has a deep meaning. I promise. |

But

Edmund is not the only one with something to express. To Phil Fish, his pride and joy, Fez,

is also a reflection of his childhood (which we can see through pictures of

a young Phil building Legos, which draws parallels to the blocky,

low-resolution design of Fez) and the

childlike wonder he experienced with games like Super Mario Brothers, Tetris,

and The Legend of Zelda. Thus, his tragic frustration when everything

seems to go wrong in the development process – including losing his fellow

developer and then fighting a legal battle over whether Phil can continue

making the game, his parents’ divorce, his father’s cancer scare, his loss of a

girlfriend, and even the crashing of the Fez

demo at a video game convention – not only becomes an affront and problem for

the game, but also Phil as a person.

This connection clearly illustrated in a brilliant sequence when the

filmmakers cut between gameplay footage of the Fez main character jumping from a cliff into a small pool of water

and then, just as the character hits the water, we cut to Phil below the

surface of a hotel pool, as if it was one continuous jump. In one quick moment, we know that Phil and

the game are one in the same. With this

in mind, Phil’s rather shocking declaration that he would kill himself if Fez was not released does not seem like

much of an exaggeration, since this game is

his life.

|

| Suicide has never been more family friendly. |

We

also have Edmund’s partner and programmer Tommy Referens who, throughout the

movie, is constantly stressed and seems quite embarrassed to be in front of the

camera. Though McMillen claims Referens

is not as stressed as he is presented in the film, the filmmakers often use

Referens to show the dark side of development, along with Fish. While Edmund seems happy go lucky, Referens

works himself to death (somewhat literally as well as figuratively, as the

filmmakers constantly focus on Tommy’s poor eating habits and insulin

injections). Thus, possibility of the

game’s failure significantly weighs on Tommy since this game has been his work

for years. His sour behavior throughout

the movie is not unfounded, and his declarations to just “curl up and die” or

just “not do anything for the rest of [his] life” if Super Meat Boy does not do well clearly illustrate how much the

work means to him.

|

| Referens |

Finally,

the same artist-work connection applies to Blow as well. Though we spend not as much time with

Jonathan in comparison to the other developers, he not only represents the

aftermath of what comes with an Indie game’s success, but also what happens

when the culture surrounding the game does not understand the meaning an artist

presents. Blow has often come under fire

for commenting on Internet threads criticizing his game (the filmmakers

representing this by not only showing Blow at his computer and the threads with

his comments, but also the negative reactions people have had to it (including

several videos and blog posts presenting Blow as a know it all or as overly

sensitive to criticism)). But, the

filmmakers choose to sympathize with

Blow’s pain and his frustration with the massive gaming audience, particularly

when they play a video of rapper Soulja Boy playing the game and being more

shallowly caught up with the time manipulation technique rather than the complex

meaning behind it. Echoes of Soulja

Boy’s review continue throughout Blow’s monologues, with a caustic “this is the

stupidest shit ever” reverberated over Blow’s saddened face. In this moment, the filmmakers truly

emphasize how horrible it is when an artist’s message is not accepted, or even considered, by the audience. For Blow, a rejection of the game is a

rejection of the self, and given Blow’s misunderstood persona in the popular

culture, it does seem he shares the same fate as his works.

|

| My game is very complex. You probably wouldn't understand it. |

Indeed,

the culture and the surrounding video games and these men is another focus of

the film, though it is much subtler. For

if we only truly focused on the developers and their side of the story, we

would not truly understand why one game succeeds or why one fails. As mentioned, the filmmakers use constant use

of internet forums, YouTube comments, and even interview some members of video

game culture outside of development, including Gus Mastrapa of Wired Magazine, Chris Dahlen of the

video game website Kill Screen, and Brandon Boyner of the Independent Game

Festival, among others. These men, and

the numerous nameless Internet commenters represent the developers’ audience

and the more realistic side of the

story of game development. These are the

people the developers are presenting their work and themselves too, and the

filmmakers show both the good and the bad.

We have the YouTube commenters, infamous for their blunt, harsh language

as they curse out Phil Fish for his constant delays on the game. As Phil vocalizes some of the more common complaints

he hears, like “When is [Fez] coming

out?” or “Is Phil dead?” we also see the more caustic comments, as one

commenter simply states, “Fuck you, Phil Fish.

Fuck you.” Other commenters on

the popular website Reddit upload pictures of Phil with sarcastic text on them,

such as “I’m Phil Fish, and I hate my life.”

Indeed, the filmmakers often try to convey how daunting the mass

audience sometimes appears to the subjects of the film. At one game convention, before the doors open

and Phil has to present his demo for Fez

for the first time in four years, the convention goers are presented in silhouette

and in profile (commonly used through the film), giving them an eerily feeling

of being a faceless, judgmental mob.

However, when things finally go well for Phil and those at the

convention enjoy Fez, we finally see the

faces of men, women, boys, and girls as their faces light up with child-like

wonder, just as Phil intended. In these

moments, the filmmakers truly try to portray what video game culture is

actually like. While it can seem

daunting and overwhelmingly negative on the grand faceless scale of the

Internet (whose role in the culture is also emphasized in the aforementioned

use of chat rooms and forums), it is the little moments of interaction, and the

moments when a creator’s message or game truly hits with the audience that

video game culture becomes a wonderful place.

As Phil laughs and chats with the players, we plainly see the dialogue

between artist and audience that is so important in any interactive and

creative medium, and we see the communication and feeling of camaraderie that

is not often associated with the mainstream opinions of video games and the

people who play them

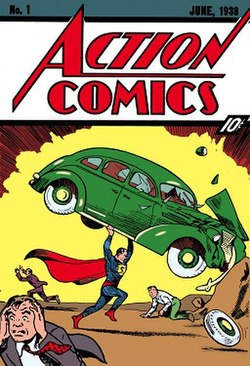

The

image often associated with Indie Game:

the Movie is a Super Nintendo controller wrapped around a telephone wire like

old sneakers, showing how video games are like a neighborhood with its own

culture and traditions. From this

culture, there will come artists who wish to use this medium to express

themselves. The film’s subjects all are

products of the video game culture who wish to share their life experiences

with the world, and, as the filmmakers constantly strive to show, only video

games (and indie games in particular) can be used to truly achieve this goal. When we look at clips of Edmund’s old projects

(with them ranging from bizarre, like a game about a creature who solves

problems by vomiting, to the just plain absurd (a penis fighting an enormous

vagina)), he explains to us that he has always been interested in pushing the

limits of what can be done in video games and in culture in general, and AAA games

(games produced and financed under a publisher) are too caught up in how a game

will sell. It is only through independent

games can people like the film’s subjects can produce such wild ideas and go

against the conventions and the norm. It

is only through this medium and lack of restriction that the audience can go

past the exterior, and we can truly learn what these men are about. In the final moments, in the “where are they

now” sequence of the film, the viewer watches as Jonathan, Tommy, and Edmund begins

production on new projects. And those

declarations are the firm example of why video games are an art like any other

medium, such as literature or film. No

matter how painful the experience is when one makes a game, the developers

eagerly jump into their project. For it

is not only a passion or a hobby, it is their life.